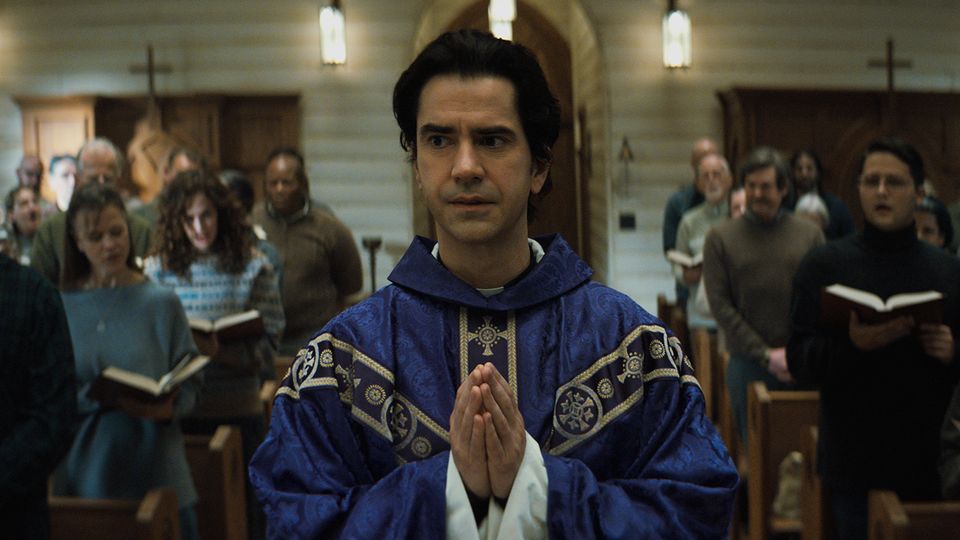

Every pastor knows that moment when you take a step back from something and take in the full extent of how things haven’t worked out as you intended. Often that’s good – you had one idea, but God has worked things differently and it’s all rather gratifying. It goes the other way too – you intended something to be one thing, but events conspired to make it something else, and now if you had the time over again you’d do it very differently. Father Paul – the priest at the centre of Netflix’s Midnight Mass – seems to have one of those moments towards the end of the series; avoiding spoilers, it’s very much the latter for him. He’d envisaged one thing; what actually happens is, to say the least, not to plan. It’s horrifying and ultimately deeply moving as his intentions spiral out of control.

Midnight Mass is for much of the time a slow, considered watch. I can’t remember a show which allows quite so much time for a long discussion about what happens after we die and on other occasions aspects of theology. Centred as it is around a Roman Catholic priest on an isolated island, it is also one of those rare shows which really seems to understand the church and faith which form the anchor of its drama; although it does ultimately become something else, it’s fair-minded and takes religion seriously. Research has been done, and many of the little details ring true. If you’re a person of faith, you will recognise yourself here.

As events take a horrifying turn, however, this is very much a show about how even the best-intentioned of people can find events running out of their control, turning into something far more sinister than they or anyone else could have dreamed of. Father Paul is clearly a man of good intention and many gifts; but so convinced is he of all this that he reads approval for his actions into Biblical texts when a cool-headed step back would see something different. But he’s high on the adrenaline of conviction, and people in those states are hard to stop; even when the alarm bells are ringing, he’s too busy and excited to hear them. He seems to have forgotten a fundamental tenet of his faith – that everybody, including himself, is prone to sin and our most basic motivations should always be interrogated. His failure to do so means his dreams for the island community he pastors turn to ashes in his hands.

We all do it, don’t we? We all have moments – be they quiet conversations over coffee, thoughts scrawled in a journal, career choices or relationship choices – when we’re swept up in the excitement of a moment and fail to examine things closely enough. Unintended consequences may be unintended, but that doesn’t stop them from being consequences. Midnight Mass starts with the dramatisation of one character’s nightmarish moment of unintended consequences overtaking him to devastating effect; the rest of the show tells the story of a whole community ultimately suffering for similar reasons in the light of a very different series of events.

We tend to venerate action and results; such things are tangible, after all. They show us we have achieved something. How often, however, are the actions and results mere noise, convenient fillers of silence that have given us something to do when we should have been focussing more on who we are? God is often more concerned with who we are than what we do, the extent to which we are living a Jesus-shaped life as opposed to the smoke and mirrors we put out there to reflect ourselves and our actions better. He’s not fooled by momentary fruit; Midnight Mass is a powerful reminder that we’d all do a little better to stop, look and listen rather more.